When the inmates of the Warsaw Ghetto took up arms on the night of 19 April 1943, they did not do so in the hope of achieving a decisive military victory. Nor did they do it to ensure their own survival. The German superiority was too great, the insurgents' equipment too poor, they were too weak after months and years of hard forced labor and malnutrition. Very few of them had ever received military training. All of them were aware of the hopelessness of their own endeavor. With their resistance they wanted to demonstrate that Jews could fight, that they would not go "like sheep to the slaughter."

They succeeded.

To this day, it is not only their courage and determination that commands deep respect from all those who hear their story; the fact that they managed to resist the murderers for several weeks in the face of German superiority seems almost superhuman. The fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto undoubtedly hold a place of honor in the list of heroes of the Second World War.

Nevertheless, the very fact that they felt they had to prove themselves to the world is dismaying. It is even more upsetting that they were correct in this assumption, for the victims of the Shoa were accused time and again of having endured their fate passively and not having sufficiently defended themselves against their executioners. Such accusations are not only tasteless, but also testify to a great lack of understanding of the powerlessness of the individual in the face of the apparatus of a totalitarian state. Even if all Jews had resisted to the same extent as the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto, they could not have stopped the German extermination machinery. Only a coalition of the strongest military powers in the world was able to do that.

The National Socialists reinforced the feeling of fear and powerlessness of the individual: this applied not only to the Jews, but to the entire population under Nazi rule. Terror was systematic and omnipresent. Focusing on oneself was often the best survival strategy, as pity for others could mean death. This was especially true in Poland, where the repressive measures against the non-Jewish civilian population were far greater than in Western Europe, not to mention Germany. While it was also forbidden in Germany to hide Jews to protect them from persecution, the punishments for doing so were rather lenient, at least in comparison to Poland, where helping Jews was punishable by death.

The tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto and the tragedy of the Polish Jews was closely interwoven with the tragedy of the entire Polish people during the Second World War. No other country suffered as much under the German occupation as Poland. In addition to the three million Polish Jews, the war and occupation claimed the lives of two to three million more non-Jewish Poles. Almost two million were deported to Germany for forced labor. The Germans systematically destroyed Polish culture and intelligence. The extent of the material destruction beggars description. Ultimately, the country lost its eastern territories to the Soviet Union and millions of people their homes. Nevertheless, the extent of this suffering is still barely known outside of Poland. I therefore understand and support the efforts of the Polish government to spread knowledge about it abroad.

Similarly, many are equally unaware of the military contribution of the Poles to the Allied victory over Nazi Germany. Even after the surrender of the Polish army in October 1939, the Poles fought on many fronts. Several tens of thousands took part in the fighting against the Germans in Iran and Italy in the ranks of the Anders Army alone, which was made up of Poles who were Soviet prisoners of war. And the Warsaw Uprising in August 1944 was an unprecedented act of resistance.

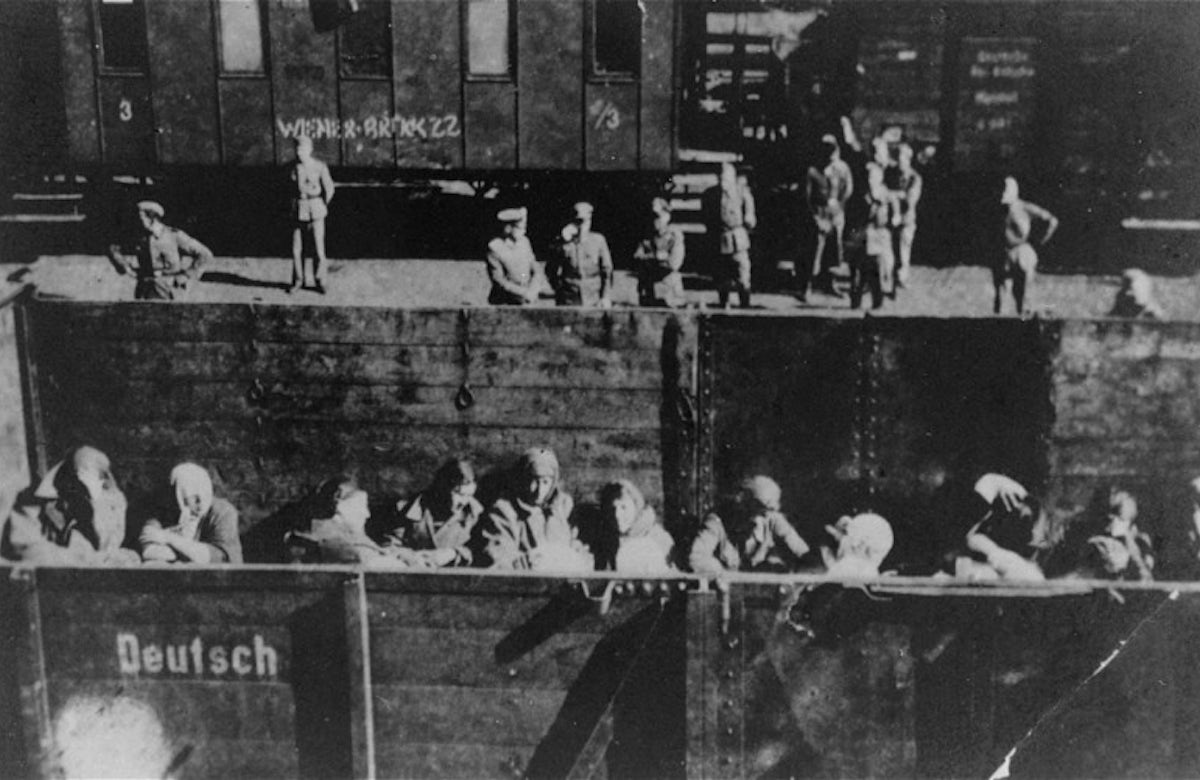

Nevertheless, the fate of the non-Jewish Poles cannot be compared to that of their Jewish fellow citizens and the rest of the Jews of Europe. For the Poles, the Nazis had planned enslavement; for the Jews, extermination. And while the Poles eventually regained their freedom, albeit at enormous sacrifice, the extermination of the Polish Jews was almost total: around 90 percent of them were murdered. The Jewish community of Warsaw, the largest in Europe, effectively ceased to exist. A thousand years of Jewish culture in Poland were wiped out within a few years. The only thing the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto gained by their resistance was death by SS bullets instead of gassing at Treblinka. In contrast, despite all the terrible constraints imposed by the German occupiers, the options open to the rest of the Polish population were numerous and their chances of survival much higher.

The behavior of the non-Jews towards the Jews also varied: parts of the Polish resistance provided weapons assistance for the ghetto fighters. The Żegota, an underground organisation founded for this purpose, saved the lives of thousands of Jews. More than seven thousand Poles are honored in Yad Vashem as Righteous of the Nations for having saved Jews from extermination - no other nation is represented so numerously in this list. On the other hand, there were also those who profited from German policies, the so-called szmalcownicy, who extorted Jews or extradited them to the Germans. And there was active collaboration up to and including support for the deportations by the Polish police, as the Polish historian Jan Grabowski has discovered.

Eight decades after the events, it is not my intention to judge. In his famous poem Campo di Fiori, the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz laments the indifference of Warsaw's non-Polish population during the ghetto uprising, but at the same time describes it as a general human attitude that is neither time- nor place-specific. Regrettably, he is probably right: we humans, with few exceptions, are not born to be heroes. And even though I do not want to downplay the widespread antisemitism of the interwar period, I do not presume to pass judgement because I myself, fortunately, was never in a comparable situation and do not know how I would have acted under the terrible conditions of the German occupation.

Nevertheless, all this is part of a complete picture of the past. Today, only very few survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto are still with us. And the remaining contemporary witnesses of the Shoah and the Second World War will also leave us in the years to come. It remains our task to preserve the memory of all crimes and their victims - Jews and non-Jews alike. However, this must be done sincerely and with an effort to be truthful. This includes naming the dark spots in our own history as well as emphasizing the unique nature of the Holocaust in comparison with the other National Socialist crimes.

The following was translated from the original published in Süddeutsche Zeitung (German), 17 April 2023.