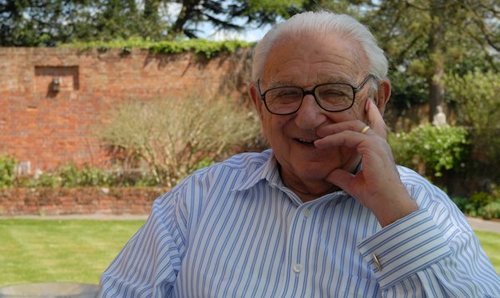

Nicholas Winton, savior of 669 Jewish children, passes away at 106

02 Jul 2015Statesmen and Jewish leaders have praised Sir Nicholas Winton, the man known as the ‘British Oskar Schindler’ for saving 669 Jewish children from the Nazis in 1939, who passed away Wednesday at the age of 106.

Winton rescued the children in Czechoslovakia at the outbreak of World War II in 1939, organizing for British families to take them in instead of letting them be sent to Nazi concentration camps. It is estimated some 6,000 people around the world have descended from the children whose escape from the Nazis Winton helped to mastermind.

Winton rescued the children in Czechoslovakia at the outbreak of World War II in 1939, organizing for British families to take them in instead of letting them be sent to Nazi concentration camps. It is estimated some 6,000 people around the world have descended from the children whose escape from the Nazis Winton helped to mastermind.

Winton died exactly 76 years to the day that the biggest Kindertransport train left Prague, carrying 241 children he helped to save.

Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said: "The Jewish people and the State of Israel owe an eternal debt of gratitude to Nicholas Winton, who saved hundreds of Jewish children from the Nazis. In a world plagued by evil and indifference, Winton dedicated himself to saving the innocent and the helpless. His extraordinary moral leadership serves as an example to all of humanity." Netanyahu sent his condolences to Winton's surviving family.

Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron declared: “The world has lost a great man. We must never forget Sir Nicholas Winton's humanity in saving so many children from the Holocaust.” The UK’s Home Secretary Theresa May called Winton “a hero of the 20th century”.

British Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis also paid tribute: “Sir Nicholas Winton was one of the greatest people I have ever met. His loss will be deeply felt across the Jewish world.” Mirvis’ predecessor, Lord Jonathan Sacks, declared: "Our sages said that saving a life is like saving a universe. Sir Nicholas saved hundreds of universes."

An unassuming hero, Winton kept details of the operation secret for half a century – not even his wife and children were aware of his extraordinary rescue effort in an operation dubbed the Czech Kindertransport. His efforts to save the children went largely unnoticed for almost 50 years, until he was reunited with a number of the children for a TV show in 1988.

Winton’s son Nick said of his father’s legacy: “It is about encouraging people to make a difference and not waiting for something to be done or waiting for someone else to do it. It’s what he tried to tell people in all his speeches and in the book written by my sister.”

Daughter Barbara said she hoped her father would be remembered for his wicked sense of humor and charity work as well as his wartime heroism. And she hoped his legacy would be inspiring people to believe that even difficult things were possible. "He believed that if there was something that needed to be done you should do it," she said. "Let's not spend too long agonizing about stuff. Let's get it done."

Winton arranged for a total of eight trains to take children from Prague, as well as other forms of transport from Vienna, and ultimately saved 669 children.

Winton was made a knight commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth in March 2003, becoming Sir Nicholas.

Last October, he was awarded the Order of the White Lion, the Czech Republic’s highest honor, by President Milos Zeman at a ceremony at Prague Castle. In his acceptance speech, Winton gave credit to the many foster parents who made the mission possible.

“I thank the British people for making room for them, to accept them and of course, the enormous help given by so many Czechs who were at that time doing what they could to fight the Germans and to try and get the children out,” he said.

Winton drew up lists of 6,000 suitable children

Born on 19 May 1909, Winton was a 29-year-old stockbroker when he decided to cancel a planned skiing trip in Switzerland in late 1938 and instead visit Prague to assist refugee workers following the Nazi occupation. When Winton visited the Czech capital at the invitation of a friend at the British Embassy there, was appalled at what he saw and realized little was being done to help the children. He set up office in his Wenceslas Square hotel and was besieged by parents desperate for their youngsters to escape. Recalling the scramble to bring the children to Britain, he said it seemed "hopeless" at the time: "Each group felt that they were the most urgent."

He had to persuade the Home Office to issue a visa, find a foster family and a £50 guarantee (the equivalent to about US$ 4,500 today) for each child, as well as raising cash for the train journey from central Europe. The British government had recently voted to allow Jewish refugees under 17 into the country, in response to the series of coordinated attacks against Jews in November 1938 known as Kristallnacht.

Dreading what fate awaited the children should they remain in a Nazi-controlled territory, Winton worked in Britain to raise funds, navigate the complex international bureaucracy, and convince families to take in the children, while colleagues worked in Prague as part of the Kindertransport program.

Dreading what fate awaited the children should they remain in a Nazi-controlled territory, Winton worked in Britain to raise funds, navigate the complex international bureaucracy, and convince families to take in the children, while colleagues worked in Prague as part of the Kindertransport program.

“One day, my father called my brother and me and he said, ‘Sit down boys, you’re going on a long journey’,” one of the rescued children, John Fieldsend, now 84, told the BBC. “As the train was leaving my mother took her wristwatch off, passed it through the window and simply said, ‘Remember us.’

Winton drew up lists of some 6,000 suitable children, publishing their photographs to try to encourage British families to agree to take them. He arranged trains from Prague to the Netherlands, ferries to take the children across the North Sea.

Eight trains and one plane carried 669 children to Britain in the months before the outbreak of war. The largest evacuation was scheduled for 3 September 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany. That train never left, and almost none of the 250 children trying to flee that day survived the war.

Though many more children were saved from Berlin and Vienna, those operations were better-organized and better-financed. Winton's operation was unique because he worked almost alone.

"Maybe a lot more could have been done, but much more time would have been needed, much more help would have been needed from other countries, much more money would have been needed, much more organization," Winton later said. Still, he rejected the description of himself as a hero, insisting that unlike Schindler, his life had never been in danger. "At the time, everybody said, 'Isn't it wonderful what you've done for the Jews? You saved all these Jewish people. When it was first said to me, it came almost as a revelation. Because I didn't do it particularly for that reason. I was there to save children."

Winton's wife Grete died in 1999. He is survived by Barbara and Nick and several grandchildren.