A return to Auschwitz, 75 years after liberation

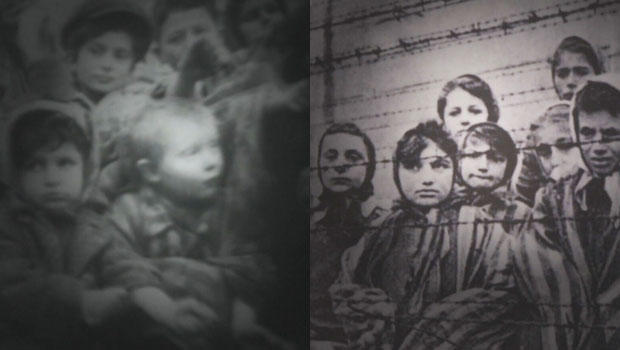

The pictures were an afterthought. Once Soviet soldiers had liberated Auschwitz in January 1945, they realized they needed a record. They needed to show the world the horror they had discovered. So, they dressed survivors back up in their uniforms and paraded them around for the cameras.

Who were they, these human beings the Nazis had reduced to numbers? What became of them?

The little boy, B-1148, four years old then? His name is Michael Bornstein. Now 79, he lives in New Jersey and tells his story in schools, showing his numbered tattoo.

The nine-year-old girl, number A-60989? Ruth Muschkies Webber, now 84, from Michigan.

Correspondent Martha Teichner asked Webber, "Did you, as a child there, understand what was happening at Auschwitz?"

"The woman told me that gave me the number that if I don't behave myself, I'll go up in smoke," Webber replied.

Webber and Bornstein were among the 200 or so survivors who went back last month to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz – their numbers dwindling. They sat in a tent covering their Ground Zero, the spot where the railroad tracks ended, where the cattle cars filled with people stopped.

This tribute to the living was also an elegy, a lament for the dead.

One-point-one-million people died at Auschwitz, most of them Jews, but also Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, gypsies, and others as well. Mainly, they were herded into gas chambers, and then incinerated in adjoining crematoria … efficiently, as many as 6,000 a day.

Auschwitz 1 was the camp with the famous gate; its motto, Arbeit Macht Frei ("Work makes you free"), a mockery to anyone who passed under it. Auschwitz 2 was its much bigger neighbor at Birkenau, where Dr. Josef Mengele carried out his gruesome medical experiments.

Just before the camps were liberated, the Nazis blew up the crematoria at Birkenau. Nearby is where they dumped the ashes of the people they killed.

You think you're prepared for what you'll see – the evidence of mass murder – but you're not, even if you've been here before. Witness the suitcases, eyeglasses, toys, a mountain of shoes.

"The children's shoes, what it says … look at this: this child couldn't have been more than two or three years old, if that. What a shame," said cosmetics billionaire Ronald Lauder, who helped raise the $40 million it cost to open a conservation lab at Auschwitz.

Teichner asked, "The 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, as opposed to the 70th or the 60th or 50th. Why is this one so very important?"

"They're all important, but this is very important, 'cause it's one of the last ones we will do when we have the survivors," Lauder replied.

Preserving Auschwitz has been Lauder's mission since his first visit in 1987, while he was the U.S. Ambassador to Austria. He is chairman of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation, and president of the World Jewish Congress.

Teichner asked him, "When you walk around here, when you see what's here to see, what goes through your mind? What do you feel?"

"Well, for me, I feel ghosts," Lauder replied. "I feel people all around me, 'cause I've been through here with survivors, and they told me, 'This is the place where my father was killed.' 'This is the place where my little brother was taken away from me.' Every place here has a story, and I've been there with survivors, and they tell me what happened."

He won't say how much exactly, but admits he's personally given tens of millions of dollars so that these objects will bear witness long after survivors of Auschwitz are dead.

"The one word that symbolizes what happened to the Jewish people was the word Auschwitz," Lauder said. "It's the largest cemetery in the world. There are a million people buried here. We are now three generations later, and what do we see over and over again is that people forgot."

According to a recent Pew poll, fewer than half of U.S. adults (45%) know that six million Jews died in the Holocaust. A 2018 study found that more than six out of ten American millennials can't identify what Auschwitz is, and more than one out of five haven't heard of the Holocaust, or aren't sure.

For Ruth Webber, the memory never goes away. Teichner asked her, "To this day, do you have flashbacks?"

"Yes," she replied.

"And from the minute you got off the train, were you afraid?"

"Afraid? I was always afraid. There wasn't a minute that I was not afraid, except when I was in my mother's arms. Or at night, when I hugged her and held onto her. I was always afraid. You never knew when something is going to happen. Never.

"You saw a German with a gun, and my mother would say to me when we passed by, 'Don't look, because if somebody sees you looking, they'll shoot you.'"

Her mother survived; her father did not.

Children would try to stay safe by hiding among the bodies. "One of the places where we had made ourselves little places where we could squeeze into was the barrack," said Webber. "One of the barracks next to us had the skeletons."

"Protected by the women around her, she remembers their anguish whenever someone disappeared. "They would say, 'God Almighty, please, please see what is happening. Let somebody survive, especially the children.' And this is what we were to do, is have a family and hopefully live long enough to have grandchildren, and to not forget that there was somebody up there that listened to all those voices.

"And I was the one that survived."

Ruth Webber did what those women asked. She has three children and five grandchildren, who could only have been born because she did not die at Auschwitz.

Michael Bornstein has four children and twelve grandchildren. He celebrates the occasions survival brought him by raising a dented silver cup, the only thing not stolen from the stash of valuables his parents buried before being forced from their home.

"And to us, it means the world," said Lori Bornstein Wolff. "To us, it stands for life before, and the life that comes."

The last time Bornstein saw his brother, Samuel, and his father, Israel, was by the railroad tracks the day the family arrived at Auschwitz in July 1944. "The memories I seem to remember is the smell," Bornstein said. "The smell was absolutely terrible in Auschwitz. And later on, I find out that it's really the smell of burning flesh."

His brother and father were sent one way, to die; Michael, his mother, Sophie, and grandmother, Dora, were sent another, and managed to live. "My grandmother hid me under straw, under a mattress," he said. "And at the end took me to what was quote-unquote an infirmary. And so the Nazis were germophobic, so to speak; they really didn't want to get into an infirmary where people were sick."

For most of his life, Bornstein, who was four when he arrived at Auschwitz, didn't speak of his time there. But after seeing his photo from liberation on a Holocaust denier's website, everything changed: "Debbie and I – my daughter, Debbie Bornstein Holinstat – were on a computer. And we see a deniers group saying, 'Auschwitz isn't so bad. Look at this picture. The kids aren't, you know, that sick.' I was outraged. We basically slammed the monitor down and we decided, 'It's time to talk.'"

For survivors, pictures from before are priceless. For survivors' children, inherited history can be a demanding legacy.

"It's a burden in a great way," said Holinstat, a television news producer, who wrote a book with her father, "Survivors Club," aimed at young adults. "It's an honor, it's a privilege that I can pass this story on to the next generation… If the next generation doesn't absorb the meaning and the importance of the Holocaust now, these memories are gonna be dust."

"Education is key to fighting deniers and people that are biased," said Bornstein, "whether they're biased against Jewish people, against Hispanics, against Muslims, against African-Americans. Education is key. Because these people get it from their parents and from areas around them. And we see it all around us right now with all the discrimination that's going on. So, we need to educate. I think that's key."

Anti-Semitic incidents have spiked in the U.S., doubling between 2015 and 2018. Amid this increasingly hateful backdrop, Ronald Lauder flew 100 survivors to Poland for the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

"We're doing this for the next generation, and for the generation after," said survivor David Marks, who is now 91 and lives in Connecticut. "It should never happen, and never again.

"I arrived here with a family of 35 by train from Hungary. And by the afternoon, I was all alone. Thirty-five of my family were sent to the crematorium."

He had never been back before. His fiancée, Cathy Peck, talked him into going, to make his peace.

"Ten hours a days we could hear children coughing, crying, choking from the gas," said Yvonne Engelmann, of Sydney. At 92, she remembers too much, such as the time she was inside the gas chamber, about to die: "The gas didn't work," she said, "so we were marched out. How can you explain that?"

She survived, and moved to Australia. "I'm here. I was able to make the journey. I'm surrounded by children and grandchildren and the spouses of my children. So, I am the victor."

For Ruth Webber, the trip was one last chance to mourn: "It makes me feel like I'm walking in the ashes of friends, and people I didn't know."

And to thank those women who prayed she would survive.

Teichner asked her, "Can you forgive the people who did this?"

"What do you mean by forgive?" said Webber. "Can you forgive somebody killing somebody else? I am continuing the life that others wanted me to. So, forgive? I live with it."

Bornstein's family clung to each other, including his daughter, Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, and her daughter, Katie. "I've never been here with one of my kids before," said Holinstat. "I just think of the, like, when people got here, they were like, it was chaos. And they did not know that they would never see their kids again."

Katie said, "If it was me, I'd probably go walking in here. I wouldn't be here anymore."

Lori Bornstein Wolff said, "My son, when he was four, it would hit me all the time that my father was in Auschwitz [at age four]. That my little boy with his cute, little bowl cut that I was buying, like Star Wars, characters for, my dad was hiding under straw and looking for potato peels. ...

"You know, in a way I feel like my kids are really lucky and they should feel really lucky. Because we shouldn't be here, right?" said Wolff. "And on the other hand, they do have a big responsibility. They should know this burden. This is our family's burden."

In 1939, before the Holocaust, there were 16½ million Jews in the world. Now, only 14.8 million, seventy-five years after Auschwitz was liberated.

Outside the only crematorium still standing, three generations of Bornsteins prayed together, a kaddish, for those they lost, and everyone else who died here.

"We are very lucky," said Michael.

BOOK EXCERPT: "Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz"

For more info:

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, Oświęcim, Poland

- World Jewish Congress

- "Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz" by Michael Bornstein and Debbie Bornstein Holinstat (Farrar Straus Giroux), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

Story produced by Michelle Kessel.